Our planet desperately needs our attention. If anything, the pandemic has proven just how much our actions harm the environment and how minimising them can go a long way in nurturing and protecting our planet. ‘Out Of The Song: Pakistan’s Plea’ is a climate documentary produced by Naveen Official, and it discusses many pressing matters regarding our climate that we need to address. Rafay Alam, Sara Hayat and Abid Omar are three of the highly knowledgeable individuals interviewed in this documentary, and it is their insight that sheds light on the issue at hand. Luckily, we had the opportunity to speak to Naveen Rizvi, the producer of this thought provoking documentary. Scroll down to read the interview, and then go watch the documentary – you won’t regret it.

Out Of The Smog: Pakistan’s Plea’ focuses on urban pollution. What made you decide to explore this topic?

In October 2018, I was in Pakistan for my team’s first filming round. On the last day, we filmed around Walled City and at the end of the 12 hours, I started feeling my throat closing up. The next day I flew back to London, and I was unwell for two full weeks. My doctor informed me it was due to the inhaled air pollution —something I’m not exposed to in London.

Through my research, I learnt how hazardous the air is in Punjab. The air pollution is present throughout the year. But, it’s trapped for a couple of months in the winter, which is why the pollution is visible. Climate Change is an all year round problem, not only during smog season.

That’s how we decided to create a documentary on the topic.

What are some of the things you discovered about climate change and our country’s response to it while collecting data and filming?

The more research we did, the more we realised how little there was out there. And the solutions imposed by the State weren’t going to reverse the scale of the smog quickly enough.

There were some articles via Pakistan’s broadsheets, but the primary source of information came from International coverage by Amnesty International and the New York Times. This made me question how aware Pakistan’s people are on how hazardous air pollution is. The most concerning thing we discovered was the number of misconceptions people had about the contributing factors to the growing smog. The media bashed the Farmers for crop burning when it only happens two weeks of the year.

The main contributors to the filthy air we are breathing is poor fuel quality and our cars with outdated (20 years) emission filters. Something that the public isn’t feasibly able to change.

Rafay Alam, Sara Hayat and Abid Omar are three of the experts you interview in your documentary. What influenced your choice to pick these three individuals?

Through my research, three names kept popping up, which were Rafay Alam, Sara Hayat and Abid Omar. Rafay has written many articles over the years and been the person written about discussing Climate Change.

I first came across Sara after seeing Jahanzeb Hussain tweet, Founding and Former Editor of Prism at Pakistan’s oldest newspaper, Dawn. He described Sara as one of the best writers on Climate Change. When we met Sara and interviewed her, even his praise-worthy tweet didn’t suffice.

I then learnt about Abid Omar, who founded the Pakistan Air Quality Initiative (PAQI). PAQI provides community-driven air quality data to increase social awareness.

I sent them each a DM on Twitter, not expecting a response. Within a few minutes, all were enthusiastic about meeting. Rafay, Sara and Abid are organisers of the Climate Action Marches which took place across Pakistan.

Sara Hayat touches on the importance of students being involved in the organisation of Climate Marches all over Pakistan last year. How do you think we can encourage students to be more involved? How can our education system be reformed to encourage this mobilisation?

The first thing schools, colleges and universities can do is show our documentary. I’m a teacher by trade, and I designed the content to be factually rich and logically sequenced. We made this documentary for the climate change sceptic as well as those who marched for the cause. We made it for children as well as parents.

To get more people involved, students and our senior citizens need to be aware of the information that wasn’t available through mainstream media but is through the documentary.

To recognise the solutions to a problem, you first have to understand the problem and the scale of it. Our documentary serves the purpose of giving Pakistan’s people the information and language to converse on the topic in an informed manner.

The inclusion of Fatimah, a young climate change activist, tied your documentary together. What prompted you to include her?

Fatimah is my niece. She is intelligent, curious, and proactive to get involved in any way she can for many causes. She was as much on a journey to learn about Pakistan’s climate change crisis as I was. And we were both stunned by what we learnt!

I wanted to include Fatimah as a voice to represent Pakistan’s children who will be growing up with Smog as a winter norm. Since the climate marches were student-led, it only seemed fitting to have Fatimah involved.

On a personal note, I take my nieces with me to interviews and meetings when they are not in school. I want them to be in spaces where they can learn from our interviewees. I took Fatimah and her younger sister to Rafay’s interview and to the Climate Action meeting. Both came with me to do their homework while I did my research for the documentary out of COLABS – Gulberg’s co-working space. At the end of the filming round, Fatimah was doing her own research on Climate Change unprompted.

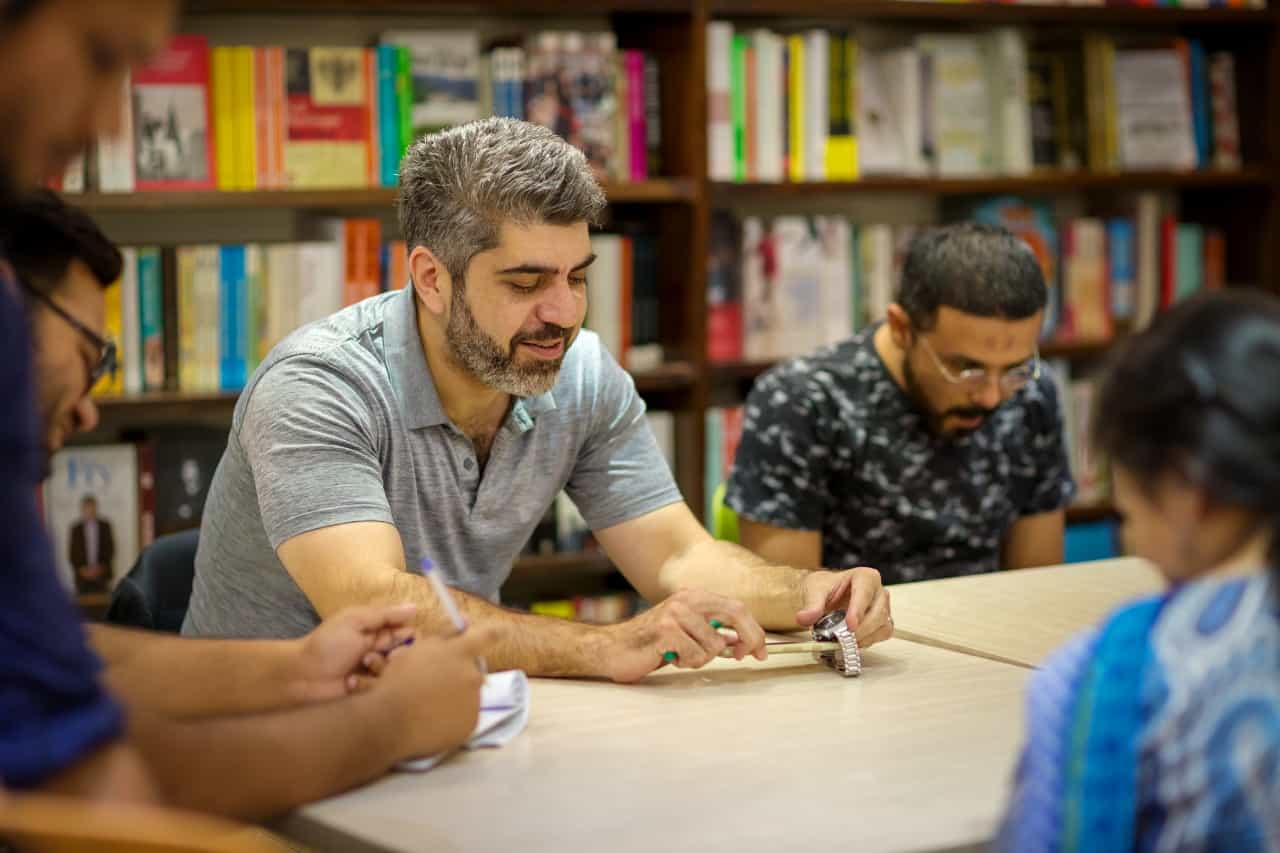

Pictured here: Rafay Alam.

There’s a cultural barrier, a kind of distrust that hinders the climate change movement, as Rafay Alam mentioned in his experience with dismissive journalists and media houses. How do you think we can combat this attitude?

This is a brilliant question. I’ve met journalists who’ve reviewed our documentary and write about climate change all year round. And I’ve met journalists who’ve seen the documentary as irrelevant to talk about until Smog season.

There is a dismissive attitude towards tackling climate change more so in Pakistan. But that’s not because people don’t care but because they aren’t aware of how air pollution affects their health. Like Rafay said in the documentary, ‘it’s a slow burn’. You don’t drop dead from breathing the air, but instead, you suffer from air pollution over time.

I hope that the documentary makes Pakistan’s people more informed to make deliberate lifestyle changes. Opting for a cycle rather than a car to get around. Hopefully, the government will start investing in public transport which is safe and clean for women and children to take. Making public areas pedestrianised. There is a limit to what an individual can do, but no limit to what a collective can do, or even the government.

As a female producer shooting a documentary in Pakistan, did you face any challenges?

There is a degree of luck that I cannot ignore here. Our interviewees have been responsive to my emails, enthusiastic, and welcoming. It speaks more of my interviewees’ kindness to have welcomed me into their homes and interview them.

Yet, there have been some instances where my efforts haven’t achieved an interview date. I’ve then had to ask my Videographer (male) to approach the person we want to interview. Fortunately, this has only happened once. But, the challenges around this are more complex and are present all over the world. The first issue is, that we’ve had an interviewee who hasn’t taken the interview seriously. For example, arriving late, being rude to me wrongly because I’m a young woman.

The second is a clash in cultural etiquette in social situations. I’ve had to be conscious of when to present my hand for a handshake, and when not. I’ve worn a shalwar kameez rather than a suit to ensure that I get everything I want out of my interview. The interviewees that I’ve worked with where I’ve been myself recognise the difference in cultural etiquette and don’t compromise the quality of the outcome despite it.

What has been the most rewarding part about producing, editing and releasing this documentary?

The most rewarding outcome is building a professional relationship with each interviewee. We’ve worked with them from pre-filming, throughout and post-production. We take interviewee feedback and consider changes that they request. I love our evolving interviewee relationship, and look forward to working together in the future.

The documentary is primarily in English. Would you consider releasing a version in Urdu or with Urdu subtitles to reach a wider audience?

This is something we are considering to change in the future. We produce English-speaking documentaries because our intended audience is the Pakistani diaspora—the 6th biggest in the world.

We plan to create an Urdu version or use Urdu subtitles in the future. We haven’t found how we can do this operationally as a team, yet.

What do you hope people take away from this documentary? What change do you wish it inspires?

The main takeaway is informing Pakistan’s people on the scale of the problem. And that we can’t buy our way out of the air we breathe.

I hope for sustainable changes such as investment in safe and clean public transport for women, children and senior citizens. I grew up travelling to school via a school bus and then taking the London Tube to get to work. Development in public transport and eradication of the social stigmas around it are crucial. I hope people opt to walk or cycle between short distances rather than taking their car.

I hope the documentary inspires our government to make some necessary changes to the fuel and vehicles we import. Also, improving emission standards for factories, clean technology and education for factory workers and farmers.

‘Out Of The Smog: Pakistan’s Plea’ is a production of Naveen Official. Can you tell us about this project and what you hope is next for you?

Naveen Official is a public awareness production house. We create documentaries specifically to promote Pakistan’s impact-orientated initiatives and individuals.

With each documentary we produce we continue developing a relationship with each interviewee. This means that we hope to touch on topics previously covered again. For example, our first interviews were with SOS Children’s village. I now know more on the topic of social orphans. I hope to create another documentary about climate change which goes beyond Smog in Punjab such as a focus on the Karachi Heatwaves.

We are currently working on our next documentary which is on Seed Out’s approach to micro finance. We interviewed the Founder, Zain Ashraf Mughal, and Operations Manager, Ali Shakeel. Seed Out has a unique and sustainable approach to support micro-entrepreneurs to set up a sustainable business through micro-finance. They operate using a crowd-funding platform where the cashless system allows people to donate online. Seed Out provides financial and business training and purchases the asset for each micro-entrepreneur. The entrepreneur pays back the loan on an interest-free basis, and that repayment is then re-circulated to a new entrepreneur. This means that an individual donates once, the borrower’s repayment of the loan then makes them the donor for another micro-entrepreneur.

Seed Out are truly extraordinary with their approach, and both Zain and Ali humbly shared their story.

What do you think?

You must be logged in to post a comment.